|

As Fracture Questions Remain, Team Raced to Save

Mississippi River Bridge

by Jim Parsons - August 30, 2021

A team of Michael Baker International, HNTB

and Kiewit scrambled to implement permanent

repairs for bridge linking Tennessee and

Arkansas

After scrambling during

the emergency, contractors were able to complete

permanent repairs in 83 days.

Photo courtesy Kiewit

"How is this bridge still

standing?”

That was the initial

reaction of Aaron Stover, Michael Baker

International’s vice president and regional

bridge practice lead, as he first studied images

of a fractured tie beam that forced the May 11

emergency shutdown of the I-40/Hernando de Soto

Bridge between Tennessee and Arkansas.

Discovered by chance earlier in the day during

MBI’s routine above-deck inspection, the

fracture on the bridge’s eastbound span affected

nearly half the cross-section of a 26-in. by

33-in. welded girder supporting one of the

50-year-old structure’s 900-ft-long, 100-ft-high

arched navigation spans across the Mississippi

River.

Though component

fractures are not unusual on older structures,

Frank Russo, MBI’s national bridge technical

director, says the de Soto Bridge crack was

nevertheless puzzling. The tie beam’s

1-3/8-in.-thick top flange plate and outer

½-in.-thick web plate were totally severed, with

the fracture extending across nearly half of the

bottom flange plate. Additionally, 9 ft of the

weld connecting the inside web with the upper

flange had separated as well.

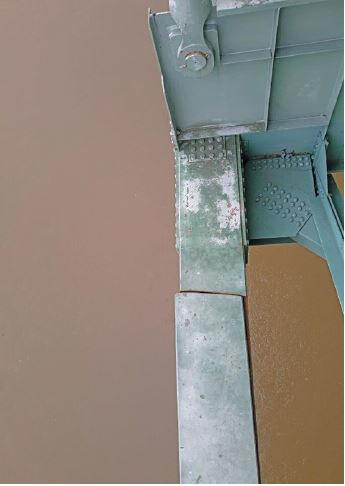

Shortly after the

fracture was discovered, the 900-ft-long bridge

spans were closed, and inspections began.

Photo courtesy Michael Baker International

“Usually when something

like this breaks, you find it completely

broken,” Russo says. “It’s very remarkable that

this member didn’t completely fracture.”

Though the fissure’s

cause and characteristics remain under

investigation, two things were clear as the

bridge was immediately closed to traffic—its

condition needed to be thoroughly assessed in

the event there was additional damage and a

repair strategy needed to be developed as

quickly as possible.

The fracture was

discovered by chance on May 11.

Photo courtesy Michael Baker International

Despite the fracture’s extraordinary

aspects, there is a strong familiarity among the

team tasked with carrying out the assessment,

both with the de Soto Bridge and each other. The

Arkansas and Tennessee transportation

departments have long shared responsibility for

the structure, with ARDOT overseeing inspection

and TDOT handling maintenance. MBI, which would

lead the response’s aerial inspection and design

work, had worked with both agencies, as had

HNTB, which performed a full hands-on inspection

of both tied-arch spans. Experts from the

Federal Highway Administration were also

involved.

The resulting bridge

section has a span of 72 meters (about 236

feet)—enough to span many rivers and highways.

Sections can also be daisy-chained and connected

into longer bridges. Each girder weighs over 50

tons, and they’re lowered carefully and

symmetrically over a pretty long time.

Traditionally constructed bridges are also often

built out symmetrically, because even small

imbalances can break the foundations that have

been constructed.

An inspector gets a

close-up view of the fracture.

Photo courtesy Michael Baker International

“It’s very

remarkable that this member didn’t completely

fracture.”

—Frank Russo, National Bridge Technical

Director, Michael Baker International

“That gave us a deep

bench of structural engineering expertise and

resources, allowing for a significant amount of

analysis and design to take place in a very

short amount of time and with a high level of

reliability and accuracy,” says ARDOT spokesman

Dave Parker.

The team also had

technology on its side, with drone video

combining with physical inspections using

rope-access techniques to expedite the condition

assessment. Drones also allowed the physical

inspection of the fracture to be streamed in

real time to the office-based design team.

“We could see what the

inspector was doing and ask to check out

additional aspects, which helped us start

planning multiple steps ahead,” says MBI bridge

technical director Jason Stith. “It was quite

incredible to get that information during a

two-hour conference call rather than having to

go back and forth over several days.”

This image shows the view

when inspectors first discovered the crack.

Photo courtesy Tennessee Dept. of Transportation

The emergency situation

for this vital connection between Tennessee and

Arkansas required work to progress on a 24/7

basis.

Photo courtesy Kiewit

Multi-path

planning

Though no additional

damage was found on the bridge, in-depth

inspections indicated that the structural load

at the fracture had been shed to the remaining

web and flange sections, putting those

components under exceptional stress.

“We needed to understand

that better before we started yanking around on

the bridge, trying to move things back to where

they were,” Stover says.

As the team began

concurrent design efforts to stabilize the

structure and devise a permanent repair, TDOT

implemented an emergency construction

manager/general contractor procurement that

agency commissioner Clay Bright says had the

capability “to get involved in the difficult,

challenging and at the time, still unknown final

repair design.”

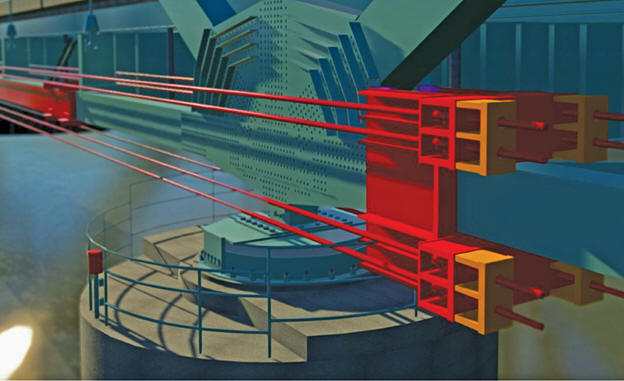

Sections highlighted in

red indicate the areas where repairs were

needed.

Rendering courtesy Michael Baker International

On the afternoon of May

17, less than two hours after TDOT had selected

Kiewit for the project, operations vice

president and area manager Chris Frieberg and

other firm representatives were discussing

stabilization and repair alternatives with the

design team.

“We worked through risks

associated with different design options and the

best way to mitigate them, as well as material

availability and fabrication lead time,”

Frieberg says. He adds that the solution had to

be one the design team could stand behind and

his team could build safely.

Rendering courtesy

Michael Baker International

“And it had to be

permanent, so that the DOTs would be assured of

having a safe structure for years to come,” he

adds.

The resulting two-phase

strategy called for first stabilizing the

fracture area with a “splint” of steel plating

that would add redundancy to structure. Because

the girder was slightly twisted and warped, the

plates would be offset to prevent placing any

new stress on the area.

While TDOT originally

envisioned basing the repair effort from barges,

the design team’s loading analysis indicated

that the fracture area could be safely accessed

from the bridge deck.

“That gave us a more

controlled environment for the delicate work we

were doing, although we did have to keep

personnel and equipment to a minimum,” Frieberg

says.

By the end of that first

week, Kiewit had assembled a 100-sq-ft suspended

platform to install the first of 30,000 lb of

HPS70W structural steel plates fabricated on an

expedited basis at Stupp Bridge Co. in Bowling

Green, Ky.

Over the next four and a

half days, crews used chain and air hoists to

lift the plates into place, where they were

secured with nearly 450 temporary bolts.

Frieberg says the work involved some lead paint

considerations and confined space protocols when

working inside the tie beam but required no

additional measures for COVID-19.

The ability to use drones

to inspect the damaged bridge aided the project

team.

From stopgap to

structurally sound

By May 25, two weeks

after discovery of the fracture, the de Soto

bridge was deemed sufficiently stabilized and

safe enough for TDOT to reopen the underlying

river channel to barge traffic and transition to

the next repair phase. A 150-ft-long section of

tie girder encompassing the fracture area would

be beefed up with 108,000 lb of additional

redundancy plating, with eight 3-in.-dia

high-strength post-tensioning rods installed

alongside the beam to transfer more than 1.2

million lb of tension to the composite section.

The supplemental

post-tensioning also allowed workers to remove

fractured flange sections for analysis.

“If the entire tie

decided to break, which is very unlikely, it has

a completely redundant element on the outside

that can carry the load,” Russo says.

Frieberg says this

strategy required an even higher level of

coordination and analysis given that the

precision fabrication of specialized

post-tensioning components and weldments and

additional strengthening plates had to be synced

with mobilizing specialty subcontractors and

addressing other logistics needs.

“We had three critical

paths running simultaneously, and the art of the

dance was keeping them all in unison,” he says.

“All three converged so that as the design was

signed and sealed, material fabrication was

underway.”

By July 3, the last of

the plates at the fracture location had been

bolted into place. But there was still one more

important step to complete before the bridge

could be declared fully restored. During the

initial condition inspection, HNTB conducted

non-destructive phased array ultrasonic testing

on the tie girders’ 500 welds to determine if

similar cracks were forming or could form under

certain conditions. Seventeen welds were found

to have anomalies, which Kiewit plated over the

next three weeks with a total of 78,000 lb of

steel to provide additional redundancy. Another

29 weld defects were ground or cored out.

“It had to be permanent

so that the DOTs would be assured of having a

safe structure for years to come.”

—Chris Frieberg, Operations Vice President,

Kiewit

After another round of

inspections, the de Soto Bridge’s eastbound

lanes were reopened to traffic on July 31,

followed two days later by the westbound lanes.

That completed an 83-day, 24/7 marathon that was

remarkably free of weather interruptions. Costs

for the routine and specialized inspections and

repairs, currently estimated at $10 million,

will be shared by both DOTs.

The effort also concluded

what ARDOT’s Parker considers to be a parallel

success story—safely shifting the de Soto

Bridge’s 40,000 vehicles per day to other

crossings, particularly the nearby 72-year-old

truss bridge that carries I-55 across the river.

Parker credits the team’s

collaborative brainstorming of congestion relief

strategies for helping cut the I-55 bridge’s

initial hour-long peak-hour backups by more than

half and reducing bail-out traffic onto local

roads. Both DOTs stepped up services to minimize

the effects of lane-closing incidents. TDOT’s

Bright notes that motorists’ initial concerns

about the safety of the I-55 bridge were

alleviated by emergency inspections and the

performance of the “robust structure” while the

de Soto Bridge was out of service.

“The only issue was a

pavement failure in one lane that was quickly

addressed during a weekend temporary lane

closure,” Bright says, adding that the bridge is

currently undergoing its scheduled biannual

inspection. “Any new issues will be addressed

along with other maintenance work next spring.

Meanwhile, the fractured

tie girder section is at Wiss Janney Elstner’s

forensic laboratory in Northbrook, Ill.,

undergoing metallurgic and other tests in an

effort to fully understand the factors that led

to the fracture. Parker says results of that

investigation, scheduled to be delivered by

fall, will help the DOTs determine if the

structure requires additional attention on top

of regularly scheduled inspections and

maintenance. A solar-powered strain gauge

monitoring system installed prior to the

bridge’s reopening also remains operational.

What’s already certain,

team members agree, is the essential role

team-wide collaboration played in turning a

potential catastrophe into a success story.

“If you listened into our

daily calls, you wouldn’t have been able to tell

who was DOT, who was designer and who was the

contractor,” Frieberg says. “Going through the

process, we were very well integrated and very

open-minded. That was the biggest contributor

with coming up with a design solution that could

be implemented quickly and safely.”

Questions Remain

in Inspection Oversight Controversy

Within hours of the

discovery of the de Soto Bridge tie girder,

images and video emerged suggesting that the

fissure had been months, perhaps even years in

the making despite having been unreported in at

least two ARDOT-led annual fracture-critical

inspections. Following an internal investigation

launched immediately after the closure, ARDOT

fired Monty Frazier, a 15-year employee who had

led the 2019 and 2020 de Soto Bridge

inspections. In addition, the Federal Highway

Administration launched an assessment and

compliance review of ARDOT’s bridge inspection

program, with the results expected by the end of

September.

Frazier’s reported

assertion that the mobile under-bridge

inspection platforms were unsafe to use was

countered by the agency’s heavy bridge

maintenance staff (HBMS), which, according to an

ARDOT interim after-action report, verified that

the equipment was stable and provided adequate

access to perform hands-on inspection at the

fracture location. Nine other fracture

structures inspected by Frazier were reexamined

and found to be safe.

Frazier has since

admitted that missing the fracture was a mistake

on his part, but he insists he’s not solely to

blame. In an interview with the Daily Memphian

newspaper, published on July 22, Frazier said he

pointed to the crack’s appearance in photos

reputedly dating as far back as 2014 as proof

that other inspectors overlooked the condition

as well. “If there are that many people who

missed the crack over all that time,” Frazier

told the reporter, “it’s a problem with the way

we inspect the bridge, not just the one guy who

happened to be on the paperwork the last time we

missed it.”

ARDOT has not verified

the validity of the photos and declined to

comment on the story. Meanwhile, multiple

investigations are underway, including an

agency-requested probe by the U.S. Dept. of

Transportation’s Office of Inspector General as

to whether Frazier’s alleged negligence

constitutes a criminal action. A parallel

internal investigation by ARDOT’s human

resources department is proceeding as well.

In July, ARDOT boosted

its historic bridge maintenance system budget by

nearly $3 million, providing funding for

consultants that will help the agency identify

new technologies, improve quality assurance and

quality control and improve inspector training.

|