|

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Masterpiece Leaning, But Won’t Be Falling

In Water by Fred Bernstein N. Y. TIMES NEWS SERVICE

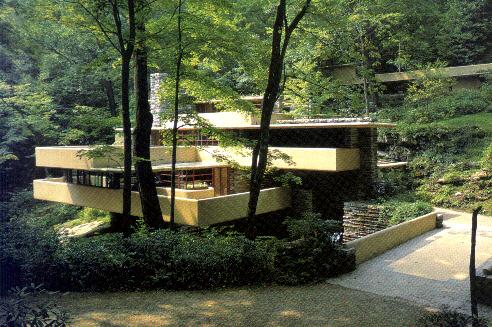

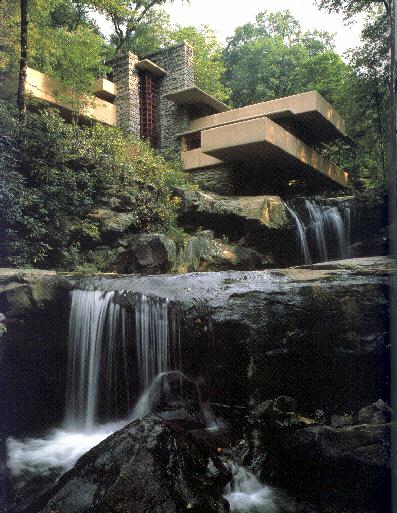

BEAR RUN, Pa. - Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd

Wright's 1936 masterpiece, has a little less far to fall. One corner of the house, slung

over a waterfall here, is more than seven inches lower than it should be, the result of

structural problems that threatened to bring the building crashing into the

rocks below.

And so, when the house opened in early March for its annual

season of public tours, visitors were treated to the remnant of exploratory surgery: a

bathtub size hole in the middle of the living room floor.

"We opened up the floor to look for cracks, and we

found them," said Lynda Waggoner, director of Fallingwater, which was voted the

country's most significant building by the American Institute of Architects in 1991.

On opening day, architecture students, looking like visitors

to an archeological dig, crouched around the hole and examined the concrete beams beneath

the flag stone floor and redwood subfloor.

Even more striking was the house's exterior, which rests on

a series of steel columns and beams unknown to Wright. The supports were installed in 1997

to stabilize the building until permanent reinforcements could be put in place.

From across the stream, the propped-up Fallingwater, which

is owned by the nonprofit Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, looks like a champion gymnast

on crutches.

Or, as Robert Silman, the engineer who installed the

girders, put it, "The main cantilever isn't a cantilever anymore."

Had the building collapsed, it might have

cracked the stone ledge beneath it (perhaps inspiring the headline "House Crushes

Boulder," the architectural equivalent of "Man Bites Dog"). That would have

been an ironic end to a house renowned for its symbiotic relationship with nature.

2-degree tilt

The droop in the southwest corner of the main

cantilever is visible from the stream. On the house's terrace, the 2-degree tilt

increases the vertiginous feeling created by Wright's unusually low parapet walls,

comparable to the low walls at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan. "Seven

inches is a lot," Silman said of the terrace's sag.

Silman, whose firm is based in Manhattan,

decided to install the girders after discussing the problem with Fallingwater's trustees.

"I told them, 'We'll have to shore it up eventually,'" he said. "'Why not

now, so your consciences are clear?'"

The most surprising thing about Fallingwater's

fate is that it could have been prevented. The problem, as Silman and others who have

looked at the structure say, isn't age, but Wright's failure to put enough steel

reinforcing rods into the concrete – despite strong admonitions to do so.

Wright's reasons for under-reinforcing the

structure aren't clear, but appear to be related to his lifelong aversion to being told

what to do. Indeed, when Fallingwater's contractor suggested increasing the steel in the

building to make it safer, Wright threatened to quit the project.

He wrote Edgar Kaufmann Jr., the Pittsburgh

department store magnate who commissioned Fallingwater, "I have put so much more into

this house than you or any other client has a right to expect that if I haven't your

confidence - to hell with the whole thing." (To those not familiar with Wright's

letters, this was mild language for the architect, then nearly 70.)

When Wright wasn't looking

Wright also maintained - wrongly - that the

weight of additional steel would weaken the structure. Nonetheless, when Wright was away

from the site, the contractor installed twice as much steel reinforcing as the architect

had asked for.

Had he not done so, Waggoner said, "the

building probably would not be standing today."

Still, he didn't add enough steel to solve the

problem. All reinforced concrete bends; there is an initial droop, often pronounced, on

the day it is poured, and a slower bending (called creep by engineers) which occurs mainly

in the building's first year, Silman said.

In this case, the house never stopped bending.

"If it was still moving after 60 years, the inevitable conclusion is that it would

eventually move far enough to fall into the river," Silman said. (The bending of

Fallingwater's concrete trays is distinct from settling, a far more mundane problem.)

At first, Kaufman - said to be worried about

the cantilevers until he died in 1955 - kept tabs on the problem, by having detailed

measurements made every year.

But after the family donated the house to the

conservancy, which opened it to the public in 1964, measuring was discontinued.

Four years ago, Waggoner decided it was

time to take another look at the cantilevers. That's when the extent of the problem became

clear. These days, movement detectors, wired to key parts of the structure, send data to a

laptop computer hidden under a bathroom sink. Each week, the data is sent by modem to

Silman.

Wright was known for creating buildings with

irritating faults— his net roofs often leaked - and many are deteriorating with age.

Silman's firm has helped save several Wright buildings, including the architect's

Wisconsin studio Taliesen, which was severely damaged after a 200-year-old oak fell

through its roof last year.

Silman's solution to the Fallingwater problem

is straightforward: he plans to drill holes through the concrete structure, then insert

steel cables through the holes. The cables will be slowly tightened, increasing the

tension in the concrete (the process is called post tensioning.)

The plan, however. won't be made final until

architects and designers have a chance to weigh in during a public forum on April 10, at

the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. "This is an icon, and I want to do it

right," Silman said. "I want there to be a consensus."

Aspirations of a century

Waggoner, whose office looks down on the

building from a Wright-designed guesthouse, said Fallingwater "represents all the

aspirations of the 20th century," adding: "These problems don't diminish the

importance of what this building did for architecture."

She is charged with raising as much as $6

million for Fallingwater projects (including unsexy jobs like bringing the drinking water

into federal compliance). Silman's post-tensioning will cost about $1 million and is

expected to be finished by the end of this year.

Waggoner grew up nearby, led tours at

Fallingwater wile in high school, then returned as a curator in 1985. On a tour of the

house, she willingly points out trouble signs, like a door that doesn't open all the way

because its frame has tilted slightly. She called attention to a ceiling fixture through

which water drips during rainstorms. "Look at that," she said. "That's not

a place you want to see a leak."

Otherwise, the house - thanks to Waggoner's

vigorous efforts— hasn't looked better in years. The structural problems don't

diminish Wright's architectural pyrotechnics.

Fallingwater's guides have one concern: that

some of the 130,000 visitors a year will drop cameras, keys and contact lenses into the

hole in the living room floor. That's one reason Waggoner is considering covering the

opening with glass.

The planned restoration of Fallingwater already

has fascinated tourists. Neil Diller, manager of a poultry operation in Fort Recovery,

Ohio, and a first-time visitor to the house, said: "It's surprising that as good an

architect as Wright screwed up. Sixty years is a long time, but not that long."

The temporary supports, the hole in the living

room floor and the candor of the guides about the problems at Fallingwater make this an

unusually good time to visit.

The house, which is about 60 miles southeast of

Pittsburgh, will be open every day except Monday. Tours start at 10 a.m. Reservations and

information: (724) 329-8501. Visitors who arrive without a reservation risk being turned

away.

This website was originally

developed by

Charles Camp for

CIVL

1112.

This site is maintained by the

Department of Civil Engineering

at the University of Memphis.

Your comments and questions are welcomed.

|